25% Off - use code: HOLIDAYS

Introducing The Blue Plate: Fighting Climate Chaos One Meal At A Time With Mark J. Easter

Watch the episode here

Listen to the episode here

How can the choices on your plate help fight climate chaos? In this episode, host Corinna Bellizzi sits down with Mark J. Easter, an ecologist and greenhouse gas accountant, to explore the impact of our food systems on climate change. Mark shares insights from his new book, The Blue Plate: A Food Lover's Guide to Climate Chaos, diving into how regenerative farming practices can restore the environment while producing healthier, more nutritious food. From the challenges of modern agriculture to the hopeful stories of farmers making a difference, this conversation reveals how every meal can be a step toward a more sustainable future.

Key takeaways from this episode:

- Discover how regenerative agriculture can reduce greenhouse gas emissions and restore soil health.

- Learn why eating locally and seasonally is better for both the planet and your taste buds.

- Understand the role of carbon-rich ecosystems like mangroves in supporting sustainable seafood.

- Find out how small actions, like choosing more plant-based foods, can have a big impact on climate change.

Guest Social Links:

Website: https://farmtablesky.com

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/mark-easter

The Blue Plate: https://amzn.to/3z5hS7d

---

Introducing The Blue Plate: Fighting Climate Chaos One Meal At A Time With Mark J. Easter

If you’re a foodie who cares about the environment, you are in for a treat. I’m joined by Mark Easter, an Ecologist and Researcher in academia and private industry since 1988. As a greenhouse gas accountant, his mission is to understand how greenhouse gasses move into and out of soils and plants on farms and ranches. He’s traveled globally to collaborate with farmers, ranchers, researchers, and foresters to learn how people grow food and fiber to make agriculture healthier and less damaging to our climate. He’s here to connect these many dots as we explore his new book, which is The Blue Plate: A Food Lover's Guide to Climate Chaos published by Patagonia Press. It is out as of September 18th. With that Mark Easter, welcome to the show.

It’s great to be here. Thank you.

Nutrition Without Compromise

It’s so good to see you again. Now, I have the pleasure of interviewing you once already on my other show, Care More Be Better. We’re going to dive in a little deeper and because you’re on this show, I decided to resurrect one of my earliest questions as I launched the show. I used to ask every guest, what does nutrition without compromise mean to you?

For me, food is just so personal to all of us and it’s hard to think about compromising when it comes to good taste, what we want to present to our families and to our friends and colleagues, if we’re hosting a party or something like that. I want the food to be a reflection of me, my family and what my values are. When I think about food, I try to focus on those values.

Whether it’s eating locally or plant-based or you know coming from the tradition that I grew up on the great plains. We call ourselves dust bowl people. There were a lot of food traditions that came out of that, so honoring those traditions and also the sweetness and the memories that come from all of that. That's what comes to mind when about nutrition without compromise.

The Blue Plate

Enjoying regional treats and embracing culture sounds like a great place to start, too. While we’re on that topic of names, you titled your book The Blue Plate: A Food Lover's Guide to Climate Chaos. I get blue, but why did you bring chaos into the title?

A lot of people have been asking about that. It’s because we’re facing more chaotic weather systems and climate systems as the climate crisis progresses. Chaos is an operative term for a lot of farmers because they have so little control over certain aspects of their farming and ranching operations. That’s largely introduced by the weather.

There are other factors that come in related to market conditions and things like that. Ultimately, what we’re trying to do is, I think, through regenerative agriculture. What a lot of people are trying to do is introduce resilience where chaos enters the equation. We also need to acknowledge that things are becoming more chaotic and pay attention to that because it’s going to have an impact on our lives in so many different ways.

Regenerative Practices

Having been and even the algae industry for the past roughly decade. I worked first in space as we were growing algae in open ponds and guess what? Rainwater introduces other species of algae. It introduces amoebas and pollutants. All of which you have to control for and some way because you want to grow a specific strain. Part of the way that we tackle that with vaxo was to move everything indoors into a tightly controlled environment.

That’s not an option for a lot of the food that we grow. Sure, it might work for some microgreens and lettuces, but when you talk about grains, how do you feed the people at the same time? This digs into some of the content in your book because you’ve even compared how you grow, let’s say grains in this more regenerative capacity and the cost of that. Versus, a more conventional way. I wondered if you could talk for a moment about that discovery and what you’ve come away with.

Exploring all the different stories for the different foods that come onto our plates was so revealing to me. Perhaps, the story of grains was the most personal because what I discovered was that some of my direct ancestors, my great-grandmother in particular, was a farmer in the great plains. She was involved in the process of trying to make a living and was involved in producing one of the greatest flushes of carbon emissions in the atmosphere in human history.

That was the plow out of the great plains in order to convert it from this fantastically rich and diverse grassland ecosystem into one of the largest agricultural complexes in the world. It became deeply personal for me. What I discovered there was that she had been involved in a farming practice that was extremely destructive. Widely practiced then and still now. It’s this process of what we call fallow wheat. Growing only wheat on the land and growing it only every other year. Intentionally, keeping the land fellow and keeping plants from growing on the land for an entire year or more than a year in order to help moisture build up for the wheat crop that would follow.

It was extremely destructive. It was profitable for a while, but the only way to prop it up to keep it going was with chemical fertilizers and other agricultural chemicals. That’s the only way they could keep the system functioning and keep it alive. There were a lot of consequences there for human nutrition. Some of that came in with plant breeding. The push to try to produce wheat crops that maximize the amount of endosperm, the material that goes into producing white flour at the expense of nutrition and flavor and other measures of quality.

Where the story turned pivoted for me was learning that the people who owned the land now had ended that destructive practice. There were no longer growing wheat in this fallow wheat system that they were growing crops every year. There was a lot more diversity on the land. They began the process of restoring the soil. Regenerating this system there. It pivoted also as well, learning through the story of other farmers in the region and a particular one called Curtis Sale’s who’s from an area not too far. About 50 miles from where my great-grandmother farmed.

He’s introduced practices that are turning things around. He had described the soil on his property as having hit rock bottom. Through the practices that he’s engaged in, he’s not just restoring the health of the soil and the health of the system. He’s producing much more nutritious crops for the human food that is growing as well as for the livestock that the grays on his land as well too that are integrated back and are helping to restore the soil health as well, too.

It’s heartening to see that. I’m personally delighted to see that the research lines up that show how regenerative practices, restoring the soil, improving the health of the ecosystems, and drawing down carbon dioxide from the atmosphere into the soil is also leading to healthier foods, better nutrition for people, and for the livestock that we depend upon.

Regenerative practices are leading to healthier foods and better nutrition for people and livestock that we depend upon.

There’s no conversation about food that can go forward in this day and age without talking about grains because grains are grown to feed the animals. Grains are grown to create nutrition for humans around the globe. The one thing I’ve always remarked on is the fact that astronauts, when they go into space. They look back and see this bright blue marble and the expanse of nothingness around it. They often come away with this sense that our planet is essentially an oasis. Planetary perspective that seems to integrate an understanding that all of these systems are connected in a much more profound and deep way.

The Blue Planet

That was the inspiration for calling the book The Blue Plate. That spinning blue marble that the Apollo Astronauts first saw. The first humans to see and the photographs that they sent back brought back with them from deep space and the moon explorations. To see that and recognize it is home and also, how incredibly fragile it appears to be and incredibly beautiful as well, too.

I often think about that and then wonder how we might help change the perspective of more people with their feet are firmly planted on this beautiful blue planet to help them understand that greater perspective. I think so much of what we end up arguing about when it comes to our global food systems, whether climate changes are real and subsidizing certain crops and not thinking about other crops at the same time. It circles back to this one challenge of not seeing everything we have as an integrated system. I wondered how your work with this book and otherwise, might help people along the way. Invite them perhaps to think a little bit more beyond the Blue Plate to the blue planet.

That’s part of the hope, one of the hopes on many hopes that I have for the book. It can offer perspective theory that goes beyond just climate change but also makes things personal for people. One of the things that’s so interesting about the climate crisis is that as a population, it’s not just here in the US, but it’s around the world. Whereas, people may be divided about the causes and the potential consequences of burning greenhouse gas emissions and creating the climate crisis.

We are pretty united around the solutions. People are excited about converting from burning fossil fuels to using wind, solar, and geothermal as alternatives to that. People are generally excited about pivoting to electric transportation and away from other forms of heating our homes and getting around. We’re starting to see the same thing with food. I think it’s so interesting that people are excited about the solutions that are coming with regenerative agriculture.

The very notion. It’s a great term calling these practices regenerative. I think it speaks to the hopes and dreams and wishes of an awful lot of people. There is so much concern about the direction that things are going and so many different aspects over our lives. As I talked about in the book, nothing is more personal than food and connecting on a personal level to these solutions through food. What presents themselves as such positive stories and such beautiful stories and changing the story behind food to something that is regenerative. It's something that appeals to a lot of people, whether or not they longed to believe that the climate crisis is real and that it is a human cause. They’re aligned on the solutions. I’m just delighted to see that happening.

Climate-Friendly Eating Habits

Reading your book also brought me back to an earlier work, which I’m now rereading, which is The Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals by Michael Pollan. He coined the phrase with that work of eating food. Not too much. Mostly plants. In your opinion, how can we eat in a way that is more climate friendly? Do we have to cut out all meats from our diets? What do you think works?

Michael’s dictum was a perfect presentation of what the solutions are. We find that plant-based foods as a whole have anywhere from 5 to 25 times less carbon emissions associated with them compared with animal-based products. Whether that’s meat or dairy with a few interesting exceptions. These are things I try to focus on in the book. From this standpoint of human nutrition, that’s the physician’s prescription. It’s to focus on plant-based products in general.

There are good alternatives for meat-based products. In particular, one that is so fascinating and this maybe presents the most regenerative picture and story behind it is farm shellfish in growing mussels, clams, oysters, scallops and farming them. We’re reintroducing these critical animals to the ecosystems where they were extirpated in the decades and centuries passed. Mostly because of pollution and runoff from farming upstream of the estuaries where they reside.

Bringing these back in, we’re not just restoring critical keystone species into these ecosystems systems, but just through the process of them growing. They’re taking up carbon dioxide and fixing it in their shells. They’re essentially creating rock from air and CO2. They have some of the lowest, probably the lowest carbon footprint between 1 pound and 2 pounds of CO2 equivalents, which is the universal measure for carbon footprints. One to two pounds for every pound of the product that we consume. It’s a wonderful story.

They don’t degrade super rapidly, so it’s not like they’re re-entering the environment so to speak. You think about the shell mittens. This is one of the waist piles that we know exists from early American-Indian days and indigenous people. We have shell mittens to extract our findings from.

For all intents and purposes, it’s become rock and will remain that way for the foreseeable future. Probably well beyond the presence of humans on the planet.

Seafood Practices

Maybe it becomes white sand beaches along with coral and things like that gradually degrade. That makes such a wonderful sense. Now, I wanted to dive a little bit deeper to be punny and talk about seafood because our oceans used to hold a lot more life than they do now. We’ve been experiencing pretty massive species decline. Our wild tuna is now 5% of their peak populations and yet, there are still MSC certified or Friends of the Sea certified supposedly sustainable tuna. That’s just one example.

Fish like salmon are essentially no longer wild in Norway and Sweden. Something like 5% of the population of salmon that comes from those spaces is now wild. The rest is farmed. We’ve entered a new era when it comes to how we’re even getting nutrition from the sea. Often, that means grown and seen at pens with lots of chemicals and feeding them soy and corn. One of the points that you make in your book, too.

There’s a carbon cost of the feed that we give to them and the cost something like, if you give an ear of corn worth of food to an animal, including fish which are fed corn mysteriously. That they might end up producing one tenth of the amount of protein from that whereas if we consumed it directly. We could be nurturing our own body. What do you think about the future sustainability of something like our general seafood practices?

That is such an important question. Many of these seafoods that we depend upon have such critical linkages back to the land. In the case of salmon, we know that part of their life cycle is they swim up rivers and then they spawn. The adults essentially donate their bodies back to the ecosystem to feed their offspring that develop eggs and eventually hatch then live in the river for maybe a year or two before going back out to the ocean again.

What we found is so fascinating is that the forests and the salmon are critically linked. The health of those forests are intricately tied to the presence of the salmon. The loss of the salmon, as you mentioned in, parts of Scandinavia and other parts of Europe, but also parts of North America. Throughout the Southern part of the Pacific Northwest from State of Washington on down and still even in parts of British Columbia, we’ve largely extra painted salmon because of dam and reservoir systems have separated them from their spawning crowns.

What we’re finding is that the forests in those areas along those streams, dependent upon the salmon, are degrading and a great faster than we see forest degradation and other places due to climate change. That has a carbon cost. That has a critical carbon cost. I asked a number of scientists and fishermen who were working on these sorts of problems in the research for the book by restoring these ecosystems not just the forest and restoring the salmon populations. Also, restoring the mangroves that are converted over for shrimp production. It has been deforested and has a huge carbon cost associated with them and tropical regions.

If we restore all of those ecosystems and return them back to the nurseries, the fish producing regions that they were, could we make up for the balance? Could we make up for producing all the seafood that we want to consume from the oceans? The consensus seems to be not yet. Not quite. Aquaculture is still going to play a role. That’s where alternatives, the sorts of things you’re talking about algae production being able to produce foods that the fish are more aligned with what the fish are used to consuming.

Rather than corn and soybeans feeding off of algae. There’s a push now to use food waste to grow insects that are more aligned with specially salmonids like salmon and trout and other related fishes to feed them with those sorts of things that are going to be better for them nutritionally. I’m all in favor of those kinds of solutions. There’s just so much of a positive future for that thing going forward.

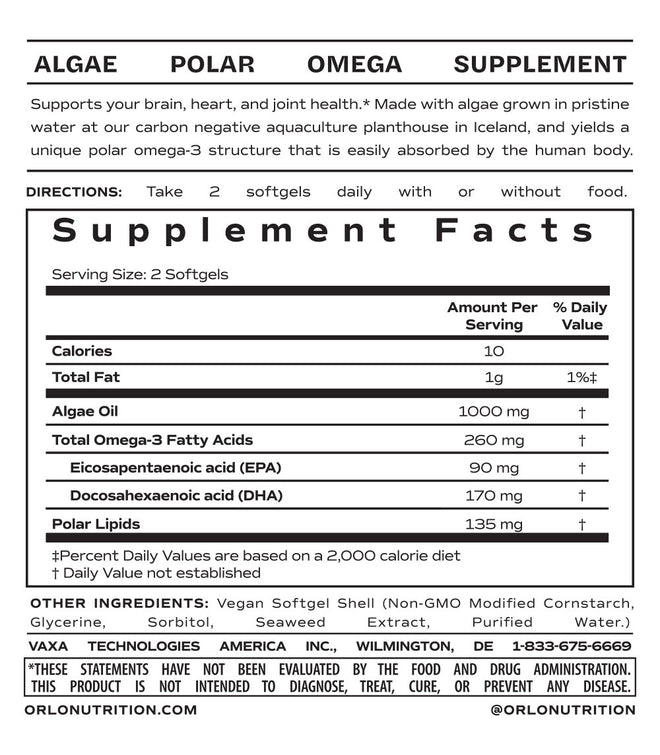

You’re speaking to some of the things we did before we were ready to come forward with human nutrition with Orlo and vexes early days. Our first products were supplied from aqua feed but that’s the parent company for Orlo. We’re growing all of our algae as well as spirulina in Iceland using as you mentioned earlier geothermal energy. There are very few places on the planet where you can capture only green energy, move everything indoors, and be able to produce something in a carbon neutral way. That’s something that we’re working to do.

I have been an advocate my whole career in the natural products industry for Omega-3s because they are so powerful for people’s nutrition. People still think, “I’m going to eat my salmon and get my Omega-3s.” They don’t understand that salmon feed these days is mostly corn and soy. There are levels of omega-6 to omega-3, the ratio is off and they’re not necessarily the best source for that anymore, sadly.

It’s also sometimes tough to tell what’s farmed versus what isn’t because something will be labeled, for instance, Atlantic Salmon. All Atlantic salmon is farmed, but it sounds like it’s the ocean. It just doesn’t say wild. I think getting people to think a little bit more deeply on those things if they’re looking for a supplement of Omega-3s. Perhaps they’ll consider algae as opposed to fish oil. They could support themselves with Orlos which is more bioavailable anyway because it’s in the polar lipid form.

It’s such a big challenge to tackle and I know there are other resources out there too in addition to your book which also artfully explains what fish are more responsible than others. I had known that farm shrimp are problematic but I didn’t realize how much so. The big bar on this chart, you have this bar that essentially shows the impact deforestation to farm them has had. Your integrating and understanding of not only the changes we’ve made to the environment to be able to form them. Also, all the processing, the fuel, the feed and the waste and all of that. Interestingly, wild salmon and farm salmon had close to the same footprint, which I was a little surprised by but you learned something new every day.

About shrimp, that was the one of the most frankly shocking findings that I came across in doing the research for the book. It goes back to the ecosystem where shrimp are mostly farmed in and that’s coastal mangroves. As we’re learning, this has just been a relatively new finding to the scientific community that mangroves are some of the most carbon rich systems on the planet.

Their carbon stores are comparable to redwood forests and other great wonderful forests of the Pacific Northwest and other temperate rainforests. It’s extraordinary and in some parts of the world even more. It’s also incredibly ironic that we’re finding that these tropical mangroves systems are some of the most critical nurseries for wild fisheries in the world. Those nurseries are so important for producing the wild food stocks.

In fact, we’re so critical for producing the wild shrimp populations that formerly were fished in these areas and much greater abundance than now. In so many parts of the world, those mangroves have been cleared. They’ve been deforested and replaced with pawns to grow to farm shrimp and other fishes but largely shrimp.

Short sighted because they also help to preserve the coastline.

We’re finding that mangroves are so important to protect the communities that are inland. Protect the coastline from sea level rise and storms. The increasingly intense storms that were experiencing. It’s restoring that and restoring the focus on the role that native ecosystems can have and producing those foods. Also, moving article culture into sustainable systems away from this. We’re essentially raising existing ecosystems in order to replace those ecosystem services with human engineered services. We’ve got to be a whole lot more thoughtful about that going forward.

Hopeful Stories

Another thing I was hoping we could close out this conversation. As we prepare for this last section of the interview, talk about the hopeful side of your research and where things have revealed themselves to be possible contributors to dampening the emissions curves that we’ve seen that are a part of the solution as opposed to part of the problem. We already know we need to restore the mangroves and maybe cut down forests to make land for great things. Mono cropping is probably not the best thing but who’s doing it right? What can we learn from them?

Those are the hopeful stories and optimistic stories that I try to present in the book. Those are the stories of the farmers and ranchers who are rewriting the story of food that they produce through regenerative practices. There’s two things that they’re doing. They’re reducing emissions. They’re reducing their reliance on chemical fertilizers, fossil fuels, and human equipment needed to grow their crops, which is all so exciting and incredibly important.

They are also doing work that draws carbon out of the atmosphere. Pulls carbon dioxide through photosynthesis back into the plants and therefore, back into the soil. Through changes in their practices allows that carbon to remain in the soil, which is the greatest repository of carbon on the planet outside of the oceans. It’s extraordinary how this thing that a soil scientist named Nikiforoff, labeled the excited skin of the planet. How this thin skin just a few meters deep holds so much carbon and is the base for our life.

There's so much optimism and positivity amongst the farmers that are doing this who are seeing the benefits coming from their resilience. I mentioned before the healthier, more nutritious food that they’re producing. It’s also making them less susceptible to the impacts of the chaotic climate that is starting to present itself through the climate crisis. A number of farmers have described it to me as a no regret strategy. Even if they were not sequestering carbon in the soil. Even if they were not reducing the emissions from their system into the atmosphere.

They see so many other benefits that are coming from it. It’s such a good and positive story. Their neighbors and others within the industry are paying attention as well, too. Seeing the benefits and the practice are expanding at some of the greatest rates of adoption if anything else in agriculture. It’s exciting to see.

There are so many positive stories that are coming forward regarding food that are arising out of the rich generative agriculture movement and other movements that it spawned.

Healthier soil, healthier animals, more resilient crops, less prone to drought, and less dust bowl situations. When we look at the extremes, you think about what led to that. We basically stripped all the windbreaks, too. We had essentially created a system. We’re allowing wind to rip through. We were not paying attention to things like the topography of the land and how we could work in concert with nature to grow crops effectively.

Now, what we’re seeing is more like the rise of small crop farmers that are doing things like selling CSAs in they’re local environments so you can get your box of vegetables that are locally grown and learn to cook something new each week. This is something that even just thinking about how people can craft their own blue plate. Trying to engage with local produce that is seasonally available will mean that it traveled this far. It supports your local community and it will probably taste a lot better and be fresher.

These are simple things that you can do to try and build your own blue plate. I encourage people to pick up a copy. I know the audio version is also now available as of I believe September 18th. They both came out, so The Blue Plate: A Food Lover’s Guide to the Climate Chaos. I will tell you that I’ve already used this in my research as I pursue my PhD in Sustainability. It’s a great tool. It’s very digestible, real, and sometimes a little shocking but such is the nature of a complex issue like climate. As we wrap, do you have any closing words that you would like to share with our audience?

I’m just grateful to be here. Thank you so much. Thank you for helping to tell the story. There’s so many positive stories that are coming forward regarding food that are arising out of the rich generative agriculture movement and other movements that it spawned. It’s exciting to see and it gives me so much hope for the future as well.

Thank you, Mark.

---

I feel like I’ve just found another resource very similar in a way to Michael Pollan’s work and I enjoyed reading through this book. I now have the Blue Plate on my listen list so I can come back to the content and absorb it in a new way. I’ll be sure to include links to where you can learn more about Mark J. Easter and his new book. All you have to do is visit this episode on whatever platform or YouTube that you’re taking this in on. You can visit OrloNutrition.com for our complete blog including features that you won’t find anywhere else.

While you’re there, I encourage you to check out our full range of truly sustainable regenerative Icelandic Ultra Algae and Spirulina products from supporting your Omega-3 levels to addressing your energy, immune system, and your brain’s function. We’ve got you covered. You can use the coupon code NWC for an extra 10% off at checkout. As we close this episode, I hope that you’ll raise a cup with me as I say my closing words. Here’s to your health.

Important Links

- Mark Easter - LinkedIn

- The Blue Plate: A Food Lover's Guide to Climate Chaos

- Care More Be Better

- The Omnivore’s Dilemma: A Natural History of Four Meals

About Mark J. Easter

Mark J. Easter (Fort Collins, CO) is an ecologist who has conducted research in academia and private industry since 1988. He received a B.S. in Electrical Engineering from Purdue University in 1982 and a M.S. in Botany from the University of Vermont in 1991.

Easter authored and co-authored more than fifty scientific papers and reports related to carbon cycling and the carbon footprint of agriculture, forestry, and other land uses. He contributed analyses to multiple reports published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

In 2018 he was named a fellow of the Colorado State University School of Global Environmental Sustainability. Besides his scientific work, Easter co-founded the organization Save The Poudre and is a founding board member of the organization “Save the Colorado.”

He works with these organizations to help restore rivers to healthy conditions and protect rivers from water development. He loves to read, cook from his garden, hike and ski in wild places, and spend time with his wife, Leslie Brown and their dog, Bonny.