Free shipping on purchases over $69

The Gut-Brain Axis And The Wisdom Of Your Body With Dr. Chris Damman, Chief Medical & Scientific Officer, SuperGut

Watch the episode here

Much of the world’s problems go back to food and public health. If we start treating food as more than the burst of flavors in our mouths and instead see it as medicine and a critical part of our health, the better we will be. Dr. Chris Damman greatly believes in this, diving even deeper to understand the science of gut health. He is the Chief Medical 6 Scientific Officer of Supergut and a board-certified, actively practicing gastroenterologist. In this episode, he sits down with Corinna Bellizzi to tell us more about the gut-brain axis and the importance of building and maintaining a healthy gut microbiome. Learn about the wisdom of your body as Dr. Chris navigates us through health, food, digestion, and nutrition. Follow along to this conversation for more!

Key takeaways from this episode

- What is the gut-brain axis

- What nutrients support the gut-brain axis

- Why you should eat fermented foods

- What is the difference between fiber and prebiotics

- Why you should listen to your body

Guest Social Links

Website: https://www.supergut.com

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/supergut/

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/chris-damman/

Gut Bites: https://gutbites.org/

---

The Gut-Brain Axis And The Wisdom Of Your Body With Dr. Chris Damman, Chief Medical & Scientific Officer, SuperGut

In this episode, we're going to dig deep into the science of gut health, the gut-brain axis and the importance of building and maintaining a healthy gut microbiome. This is critically important since nearly 40% of adults suffer from a functional gastrointestinal disorder. Before you doubt this statistic, understand this conclusion came from a study of 73,000 people and 33 countries around the globe.

This conversation started when we met Marc Washington, who is the CEO and Founder of Supergut. We get to geek out with their Chief Medical and Scientific Officer Dr. Chris Damman. He is a board-certified actively practicing Gastroenterologist, who holds an MD from Columbia University and an MA in Molecular Biology and Biochemistry from Wesleyan University. Prior to joining Supergut, Dr. Damman worked at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, where he led its $40 million gut health initiative.

He maintains an academic appointment with the University of Washington as a clinical associate professor advising the Department of Medicine and global health chairs on food and microbiome topics. Before I invite him up to the stage, I do have to remind everyone here that when we dig into the science of nutrition, we are doing this for informational purposes only. If you have a specific health concern, you'll want to connect with your healthcare provider. With that, I'm going to welcome Dr. Chris Damman to the show. Thank you for joining me.

Thanks, Corinna. It could have been worse. It could have been otolaryngology. Thank you for the kind introduction. It’s great to be on the show.

I went on TikTok to share my new yellow tear moment where I offer reflection before big moments. I sat down and tried to say. I stumbled and I'm like, “We're going to talk about digestion,” which does relate a little bit more to what most people would understand about the whole system. From the intro, you're a very busy doctor. Can you share a 30,000-foot view of what led you to this moment and why?

I've always been fascinated by what makes the world go round. I have a curious mind, trace that all the way back to the musings of a five-year-old in our backyard looking up at a willow tree and thinking about what things I might be able to craft the branches into. A real fascination with the microbiome specifically began back during medical school. It was a key lecture. There was a book that was highlighted during the lecture by Paul Ewald called Plague Time. It's a book that postulates that many of our chronic diseases, whether it be cancer, metabolic disease or neurological disease were rooted in imbalances and microbes and not in the usual sense of this microbe causes this disease but whole communities of microbes.

That idea captivated me. I suppose there was a term called the microbiome but people didn't throw it around like they do now or gut health. I followed that fascination through internal medicine and then ultimately to gastroenterology. There was a key decision point there about whether I was going to go into infectious disease, which would make a lot of sense. I was interested in microbes versus gastroenterology. For me, do I explore the jungles of the world and public health with an infectious disease or explore the jungles of the gut? It was the gut that ended up winning out.

As fate may have it, I ended up on an interesting path to work at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. I did end up in a public health role after all. I was working with women and children with malnutrition. The midst of that became inspired by this double burden of malnutrition where truly there are equal parts obesity and diabetes, as well as conventional stunting, wasting and malnutrition. I realized, “If we're going to solve the world's food and public health problems, there is a lot of work that needs to be done right here at home.” I met Marc Washington at that time. He was working on fiber-based food and the rest is history. I’m excited to explore these topics further with you.

As you've explained this path, it would automatically lead you to learn more about nutrition during your medical degree exploration all that time. How much do you learn about nutrition in med school?

My honest answer is not enough. I can probably count the number of days of learning about nutrition, maybe on my fingers even. One would think within a gastroenterology fellowship, you'd learn even more but it's not true. There probably is a lot that can be done to augment the current curriculum and medical school and beyond with additional medical nutrition themes. It truly is a deficit. It's curious because modern medicine arguably had its roots, food and properties.

They said, “Let food be thy medicine, medicine be thy food.” Even at its foundation, there was this understanding and realization that food is supercritical. You are what you eat literally, not just figuratively. There's a long way to go there in terms of our medical education but there are certainly lots of opportunities to learn in the margins. That's been my inspiration throughout my career.

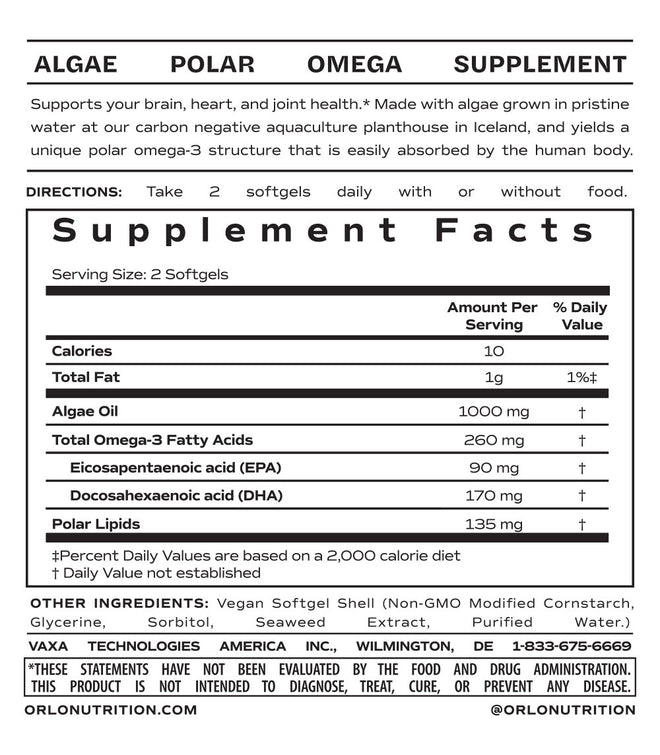

You're touching on the topic I covered with Marc Washington as we talked about, specifically, one concept, not that we are what we eat but we are what we absorb. At Orlo Nutrition, that's something that our sponsors focused on to, creating nutrients that are in their most absorbable form so they can do the good that your body needs to be done, omega-3s and polar lipids, spirulina that contains naturally occurring methylcobalamin. A form of vitamin B12, it's hard for vegans and vegetarians to get enough up.

If I'm thinking about this with the overall concept of my interview with Marc Washington focused on essentially better nutrition, better digestion equals better health because if you have the ability to absorb the nutrition from the food that you're eating, your cravings could subside, your health overall is going to be more protected, you'll have the building blocks that you need to build healthy cells to support a healthy microbiome and all of those things.

I wanted to focus on gaining a better understanding of the gut-brain axis and how the right nutrition and supplement regimen and the right types of supplements can support our health and our longevity so that we can have the best healthspan. I’ve interviewed Dr. Maroon on some of our first episodes and I've collaborated with him over the years. He said he wants to die young as old as possible.

I tried to get that quote right a couple of times and I get it wrong like, “What did you say?” He wants to feel young and vivacious up until his dying day. He lives out the truth by running Ironman. He does Ironman triathlons, runs a full marathon, cycles 100 miles or a huge amount of space in time and completes those as number one in this class, which is in the early ‘80s, not many people are doing that.

It's profound. In some ways as a society, we have thought it's a foregone conclusion that as we get older, we get sicker. The truth is that's not necessarily the case. You don't have to go hand in hand. There are plenty of examples of societies around the world in history where aging doesn't necessarily mean a collection of chronic diseases. Some of the examples would be in the Mediterranean and the island communities, Okinawa, Japan, Loma Linda, California or the quiet Peninsula and in these communities people disproportionately live to 90 to 100 years old and are relatively healthy up until the last day. I'd love it if we could reformulate our thoughts around this. Discussions around nutrition can help.

Dr. Joel Fuhrman, in our episode, said he thinks it should be the norm that we reach 100 to 105 years old. If we have the right nutrition and we aren't medicating ourselves with 5 to 6 medications, by the time we're 50, that could be on the horizon. We need to retool our overall approach to diet nutrition. He also focuses on mostly plants and not too much like Michael Pollan. If we get to this conversation specific to the gut-brain axis, what nutrients do we need to make sure that we get enough to support that? If you could define what the gut-brain axis is for us.

One can think of the gut-brain axis as almost an information superhighway that has two directions to it. It’s both going to the brain from the gut and from the brain to the gut. It's more than just a single type of communication that's happening. Some nerves connect the gut and the brain. It is called the vagus nerve. There are arguably more neurons, perhaps more neurotransmitters. I've heard the need to look at the peer-reviewed literature on whether this is in fact true, maybe more than in the brain but certainly, there are a lot of neurons in the gut. That's one connection.

The other is our immune system communicates from the gut to the brain. Lastly, some hormones are produced in our gut. Those are able to filter into the brain. It's almost like a 3-lane, 2-way highway. It makes sense because the foods that we eat need a way of coordinating how the body responds to them. It's not just the gut-brain connection. It's the gut-endocrine connection.

They got a cardiovascular connection. All of these axes are truly critical for according to processing in the body but the brain is the important one. It's the center of cognition. It is the executive function of our body. It's what tells us when we're hungry and when we're not hungry, whether we have an elevated mood or down mood, whether it's time to be active or time to rest and repose.

As we think about this, using what we think of as our brain, how would you say that the brain dictates digestion or that the gut dictates digestion? Is it a combination of the two? What do we know about that?

We know that both in model organisms and people psychologically stressful or physically stressful states impact the health of the gut and specifically can impact things like tight junctions and mucus production. Those in turn impact how happy and balanced the microbes are and how much inflammation there is. For example, if you're going through a stressful period in your life, you may experience that as changes in your bowel habits, maybe looser stools.

That's experientially what might happen or if you pull an all-nighter for one reason or another and that lack of sleep can, in some people, cause GI disturbances. That side of the connection is real but it goes the other way too. That's what we're talking about how the gut is sensing our environment through the foods that we eat and communicating to the rest of the body to prepare for digestion or other states to respond to those nutrients coming in.

Are there specific nutrients that our system needs for that to work well, to your knowledge?

Yes. When we think about nutrition, normally we think about the macro micronutrients. These were the great discoveries hundreds of years ago of folks that defined protein, carbohydrates, fats and the subtypes thereof, as well as the vitamins and minerals. That led to a revolution in food that in our modern day, we don't quite appreciate anymore but truly solves things like food security to a certain degree, yet we still have these problems but much mitigated.

Where the next couple of decades in nutrition science will go, the next great horizon is understanding what some have labeled the dark matter of nutrition. The things that are beyond the macro and micronutrients, others have been labeled as the bio-actives. These are the things that are the messages, maybe nature's packaging and instructions on how to use these macros and micronutrients. It's the regulatory pieces of food.

These include what I've labeled the Four Fs. It's an imperfect system because one of those Fs is a phonetic F. It's phytonutrients. If you bear with me, Fibers, PHYtonutrients, good Fats and Fermentation products would be those four things that probably are important beyond the standard macro and micronutrients, both indirectly impacting our microbiome or gut health but also impacting the body at large.

When people say eat the rainbow, what they're actually indirectly saying is eat lots of good phytonutrients.

Let's break this down for people so that they understand first what a phytonutrient is versus something like fiber or fat. With fermented products, we can give a few examples of that as well.

If we start with phytonutrients, one subtype of phytonutrients is polyphenols. They're often the compounds in food, the natural compounds that give them a color. When people say, “Eat the rainbow,” what they're indirectly saying is, “Eat lots of good phytonutrients.” That's one class of compounds within the dark matter of food that we're understanding better, researching and trying to understand how that fits into overall health.

Fibers certainly are another important piece. Those are found in plants like phytonutrients, the colorful foods that provide phytonutrients. Vegetables, fruits, nuts, seeds and beans are the foods that are providing us with fiber. There are different types of fiber. You've probably heard about soluble and insoluble fiber. One paradigm is particularly useful for understanding fibers, whether it's fermentable or not fermentable and people have conflated fermentable fiber with soluble fiber but it's not true.

Rentable fiber can be both soluble and insoluble. These are the fibers that tend to be more functional. In terms of fats, fat has probably every other nutrient at some point in history been vilified of it but we're coming around to realizing that no fats are good. Maybe we get too much of some and not enough of others. That's what makes things good or bad, how much we're getting of them. Beyond the nutritional properties of fat, there are functional properties too.

The instruction part of nutrition tells us when it's time to wake up to metabolize and when it's time to sleep, when it's time to be more inflamed or time to be less inflamed. Lastly, there are these fermentation products. One that we all know is alcohol, which might not be one of the healthiest fermentation products but another is vinegar. Vinegar has real functional properties, as does its cousin butyrate. Butyrate largely made in the gut by our microbes is found in some fermented foods as well.

Many probiotics are found in fermented foods. In an earlier episode, we got to talk with the Fermentation Queen herself and get to discover how you would even go about making your cabbage-based sauerkraut. It doesn't necessarily require you to even use vinegar if you're making a live food. It's interesting as we explore even some of what is presently offered at the finer grocery stores. Even at Costco, I see this fermented live cabbage sauerkraut available in their refrigerated sections. We can explore some of these things a little bit more easily as time goes on. Some of them are even nice to make ourselves and not overly complicated.

There certainly are pretty simple approaches to making fermented foods. It doesn't require adding the already-formed vinegar but letting the microbes do that on their own. In a lot of fermented vegetables, you add salt, which helps control which microbes are able to survive and thrive and which ones are less able to survive and thrive. There are tons of different types of fermented foods out there. There are fermented cabbages like Kimchi and sauerkraut or your fermented vegetable of choice, fermented grains, which are used quite commonly, at least historically in Africa by women of childbearing age meal. For children, forages that are fermented overnight that is based on grains.

There are also fermented dairy products and even fermented meats. As it's important to eat a diversity of colors, Rainbow, eat a diversity of foods, it's probably important to eat a diversity of fermented foods and probably historically ate a lot more because we didn't have refrigerators. We kept things in a root cellar, which may have been imperfect and things would grow over time. Historically, we probably ate a lot more fermented foods, even though we may not have been doing it intentionally.

To be clear for people so that they understand what we're talking about with fermented dairy, for example, you have your yogurts with live bacteria. You have things like Kefir like a yogurt beverage. You also have something like an over-the-counter product that's a supplement that's refrigerated based like Bio-K, which is a supercharged yogurt with a lot of Bifidobacterium within it and lactobacterium. In addition to that, let's not forget the cheese.

Cheese is essentially a fermented product. One of the fermentation byproducts of cheeses like Gouda and Brie is vitamin K2, which is vitamin K and its most bioavailable form, which directs the use of calcium in the body. There's this researcher, a naturopathic doctor named Kate Rheaume-Bleue out of Canada, who wrote this book called The Calcium Paradox, which postulates that the French paradox isn't about the wine. It's about the consumption of vitamin K2 to through their fermented cheeses, which meant that they didn't get clogged arteries. The calcium itself goes to the bones and teeth where it's needed to maintain the structural integrity of our bodies and out of the soft tissues where it can pose problems.

For those that consume a vitamin D product out there, please look for something that contains vitamin K2 as well or make sure that you are doing things like eating fermented foods and also getting plenty of green leafy vegetables because if you eat green leafy vegetables daily, which are high in fiber and have other phytonutrients in them that are supportive, they also contain vitamin K1, which has a shorter residence time in the body but which is as helpful and directing calcium so it goes where it's needed most. Stepping off the vitamin soapbox for a minute.

Can I propose yet another potential solution to the French paradox?

Yes.

This is an area that I've become fascinated by and there isn't a whole lot of literature on it but it may be an area that's ripe for exploration. That is dairy products in general, fermented dairy products specifically, tend to have butyrate in them, even milk. Butyrate is a saturated fat. It is a short-chain saturated fat so it only has four carbons as opposed to long-chain ones. Where does butyrate come from? It comes from fermentation. How does it get into cow, goat or even human milk? It's from fermentation in the gut.

Cows eat tons of grass, especially grass-fed cows, as do other ungulates like goats. They put that butyrate, that fermentation product into their milk. This hypothesis has inspired me to perhaps an alternate or complementary solution to the French paradox. The other cool thing is when you ferment stinky cheeses, which are perhaps a big part of the French diet. The microbes that are fermenting those cheeses, part of the reason that they are stinky is the production of short-chain fatty acids like butyrate. I'm intrigued by this possibility, certainly vitamin K and other fermentation products. It's probably more complex than a single thing but I wonder if butyrate is contributing.

That has me thinking also about Nattō, which is a vegetarian source of vitamin K2. Narrow Pharma was a company out there. They go by a different name but they have a menaquinone 7 vitamin K2 which is in many supplements across the board. It comes from either the fermentation of soy or the fermentation of chickpeas or another vegetable matter. You can produce a non-GMO vitamin K2 derivative from a vegetarian source as opposed to from cheese. They're also quite stinky. Is it the same thing?

Curious question to Nattō I believe is fermented by a bacillus. I might be wrong on this but it's like bacillus Nattō or something along those lines. I could be wrong. It'd be interesting to look at the metabolic capacity of bacillus versus lactobacillus. Lactic acid bacteria are most common in dairy fermentation and I wonder if it might be producing better, I don't know. Probably after this, I'll jump on Google and figure it out. You've inspired me.

Leave it to Dr. Google and research on PubMed before you dig into some pretty interesting wormholes.

Maybe check GPT.

If we get the right balance of these florae and our microbiome, what are some of the benefits that you tend to see from people that you've worked with and also what you're doing presently?

The gut arguably is a gateway to nutrition. I'm a gastroenterologist. Maybe I'm a bit biased but poverties is credited with having said that God is the root of all disease. I would take more of a glass-half-full perspective on that and say it's the root of health because it's through the gut, that about every molecule on our body, barring oxygen gets absorbed into our body. It's impacting the body in a super fundamental and profound way.

If you take that perspective, then about every system within the body is going to be impacted, whether it's neurocognition in the brain, metabolism by the endocrine system or allergy and immunity and protection from microbes and our immune system, certainly musculoskeletal system, like the cardiovascular system as a pump. These are all ultimately connected to the gut because every molecule within them originates from the gut.

Think about this from the perspective of supporting mood health. For example, somebody has a terrible diet overall. They're eating Krispy Kremes, white flour, simple sugars, not a lot of vegetables and chicken nuggets for their protein, let’s say, the parent on the go raising young children making freezer food. They would potentially suffer from diseases that are associated with poor digestion overall. It could manifest as poor mood, irritability and poor sleep. It's a couple of examples that compound together. What do you think this might have to do with the specific consumption of fiber? Is it that they need more fiber along with all these other phytonutrients or is it that it's the consumption of these white flowers and sugars that is super problematic?

Ultimately, what makes something good or bad is the label that we put on it. It's a label in the context of whether we're getting too much of it or too little. The calories that are in white flour and sugar, these forms of calories solve food insecurity. The reason we have refined sugars is it allowed for shelf stability and a good cost of goods, the turn of the century, removing the brand from rice. We made it possible to feed a growing population.

Ultimately, what makes something good or bad is just a label that we put on it.

There are flip sides to that. We're experiencing that in a big way in our society with the blossoming of metabolic diseases like obesity and diabetes, hypertension, high cholesterol and maybe even chronic neurocognitive diseases and inflammatory diseases. Where does fiber fit into this? Fiber is one of the many things that's been processed out of whole grains and removing the brand.

Fiber normally plays important role in conducting metabolism. It does this in part through the microbiome. It gets converted to short-chain fatty acids like butyrate. Butyrate stimulates natural gut hormones like GLP-1. It's the same hormone that you're seeing in all of these conversations around goby and the blockbuster weight loss drugs that are quite in vogue and controversial. Fiber is a natural way of stimulating those.

Those are powerful because they are right at the root of what makes metabolism work and what regulates metabolism. Fiber and other things have been taken out of food like potassium and some fats that serve a similar function. In the absence of those, the metabolism is maybe a little bit confused. This could be one of the roots of a lot of chronic diseases.

You mentioned that the brand is removed from all these different whole grains that could be health stabilizing and also ensure that people can survive a winter without a lot of fresh fruit, veggies and meat sources, things along those lines to when we're in the leaning of the winter. We're not in that position anymore and yet the shelf-stable foods that are replete of fiber are what is an easy grab-and-go style food.

We also engineered fats to remove omega-3s from them to improve their shelf stability, which is part of the reason we have such an imbalance, more omega-6 and 3, yet if you do get grass-fed cattle and they eat the whole grass, they get a balance of omega-3 and 6 in their diet. The meat itself has a better balance of the two so people can support long-term health a little bit more effectively than something that is corn-fed, corn-finished, grain-finished and more refined capacity.

I understand from my conversation with Marc Washington that while he is supportive of going to more of whole foods bases that part of what you're doing with Supergut is working to bring the science forward so that people can take that grab-and-go bar or shake and get a lot of the health-promoting benefits of prebiotic fibers to add in and even replace some of what might be more junk food. Talk to us about specifically, fiber and prebiotics. What's the difference? How do these work? What are you seeing in the scientific literature as time goes on?

To highlight your point about whole foods versus adding things back to processed foods, it's an important point and one that I want to emphasize. We've been stressing the importance of whole foods for decades but behavior change is incredibly difficult. Some tides and forces are moving against whole foods as well within the business context but even our busy lifestyles make it difficult to prepare those foods.

I embrace the 70/30 rule. If we understand what it is about whole foods in a more complete way and those bio-actives, we can maybe design foods that are convenient and tasty, maybe not whole foods but approximating 70% whole food and accommodating our lifestyles and allowing us to have our cake and eat it too. If you add fiber to high glycemic index foods that will mitigate that, you'll have less of a sugar spike and truly will be incrementally healthier for you.

The same thing is true if you combine fats with them but often people are concerned about getting too much fat in their diet. Slowing down the digestion is half of the battle in that case. If you're eating an apple, ate the whole apple, eat the peel, you get the fiber with it and then put a little bit of peanut butter. I use and prefer almond butter. With a little bit of almond butter on it, you're getting protein from the almond butter too. It's not super fatty. They're healthy to eat a little bit.

It can slow down digestion. I also consider that the perfect travel food because an apple is packaged in its beautiful, shiny, lustrous packaging. You can take a little bit of peanut butter, almond butter or your favorite nut butter with you on the go. It's not complicated. You don't have to worry about, “Is the airport going to have something that I can eat?”

I've read that the majority of the apple microbiome is what we throw away. A lot of the micros especially in organically produced apples are in the core. I've taken to not throwing much away other than this stem from an apple. I'll eat the whole thing.

The majority of the apple's microbiome is what we actually throw away.

Including the seeds because don't they also have inborn, is it cyanide or arsenic?

I've heard that before. That's true but it's a minuscule amount. Most people, unless they're eating tons and tons of apples, will be fine. You had packaged in their back a bit. With the question about prebiotics versus probiotics, I wanted to make sure that I answered that as well as the relative benefits. Probiotics have been studied in different conditions. There are nice reviews that summarize the greater evidence that exists for different conditions like traveler's diarrhea, for example, and they're taking a probiotic and where Pepto Bismol has been shown to help prevent traveler's diarrhea.

It's a stress response.

Maybe in part but also from infections. Work that's been done around probiotics and IBS, there's quite a few studies have been done and maybe some strains work a little bit better than others. Bifidobacterium, if you look at the complement of studies, may be working a little bit better than some of the other species. There is a role for probiotics within the gut and whole health. I tend to lean more towards fermented foods and the live ones that are in the refrigerator section, which have a lot of lactic acid bacteria.

There's a study that has been done by Justin Sonnenburg out of Stanford that looked at fermented foods and found that they increased diversity in the gut and decrease inflammation in the body. It's one of the better studies that has been done looking at fermented foods/probiotics in their impact on health. I am also a big fan of prebiotics. That's where fiber fits in. Fiber is what supports a healthy gut ecosystem and microbiome.

It's one of the key factors that the microbes in the gut thrive on. Certainly not the only one but probably one of their preferred food sources. To have a healthy gut, consuming prebiotic fiber, in the context of whole foods and if it's difficult to get enough there, then maybe some supplementation, combined with fermented foods is a nice strategy for promoting gut and whole health.

Let's say, I don't know a ton about prebiotics versus other fibers. We might have heard a bit about soluble versus insoluble fiber and also prebiotic fiber. How do you classify these? What makes their function different?

It boils down to whether or not the microbes love to consume them. If the microbes can have a feast on the fiber, then they're prebiotic fibers. It's that simple. The reason why we haven't classified fibers in this way, historically, is it's not a simple biochemical test, like determining whether something is soluble or not. It's more nuanced. This is a new science too. Maybe in the future, we will have things categorized this way on a food label. That's why historically, it hasn't been there.

Not all fermentable fibers should be created equal. There are some which might fall into the category of high FODMAPs. These are fibers that are present in whole foods, supplements or in processed foods that are more readily fermented in the upper gut. Fermentation in the upper gut probably isn't as helpful. It can cause gas and bloating, even diarrhea and is one of the proposed causes of Irritable Bowel Syndrome or IBS. These are fibers like insulin, which tends to be a high FODMAP, Fructooligosaccharides, Galactooligosaccharides and a lot of fibers that have good properties for going into processed foods. They're easy to formulate. It's easy to make food with them.

I've even seen supplements with insulin in them. Would you say that that's not necessarily something that's super health-promoting in that case?

It depends on the individual and what microbes they have. It's important to listen to your body. For some people, it is probably okay. They're good prebiotics. They grow Bifidobacterium. They support some people's healthy gut microbiomes. Other people may be growing organisms that are in the upper gut and causing issues. Maybe those that have small intestinal, bacterial overgrowth or imbalances in the upper gut.

Listen to your body.

The advice I give is to listen to your body. If you find when you're eating foods that have onions, take a close look at the food label. That would be things like garlic powder, onion powder as well or super high and insulin or even whole foods soup that has garlic and onion. If you find that you feel crummy, bloated or maybe foggy-minded afterward, your body tells you something.

I remember my mother’s French onion soup and it would cause her to have incredible gas afterward but it's delicious. We do listen to our bodies but we also have things that we enjoy and find to be comfort food. For me, moving away from milk has been hard because I love milk much. I have also found that I am sensitive to it. This was revealed through some blood tests. I've started to consume less dairy in general.

One night, I decided I was going to have some beautiful cheese base ravioli. They were delicious. I paid the price. I woke up not feeling right, bloated and all that jazz. I sent myself to the bathroom earlier than normal in the morning for me. As it stands, we have to be careful about certain things for us. Let's say, we might have been mildly sensitive to something in the past but then we stopped eating it. I was mildly sensitive to milk and I stopped consuming milk, now the cheeses that are closest to milk like ricotta are the ones I'm having the deepest problem with. I'm not likely to be able to go out and have a tiramisu anymore because I stopped consuming milk or cannoli. I’m not going to enjoy that either even though I am Italian. I'm going to step away.

With that being said, I seem to be fine working with cheddar, Gouda or something more of harder cheese like Parmesan. I haven't said full stop no dairy but I'm having to be more selective with time. Given that, are there some things we can do from a microbiota perspective to reduce our sensitivity to some of these would be allergens or things that are becoming creating food sensitivities for us?

It's a tricky problem because the solution historically is elimination. That's true with FODMAPs. The trick there is you eliminate all FODMAPs and then sequentially bring them back. Within inflammatory bowel disease, experimental therapies are looking at very low carbohydrate diets, which eliminate carbohydrates almost entirely.

You mentioned FODMAPs. What are they?

It stands for Fermentable, Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides and Polyols.

What that's used for is to help us discover where food sensitivity lies through elimination and things along those lines.

In simple terms, these are certain types of fermentable fibers that are present in food and some people who have IBS might cause bloating and symptoms. If you eliminate them, then you might feel better. There's a canonical celiac disease where you eliminate gluten that's a bit of a no-brainer or lactose intolerance. In some of these conditions, elimination is critical. You have an immune response to gluten and true diagnosed with celiac disease. Try as you might reintroduce, that's never going to change. You're always going to have that immune response.

In other conditions, it may be one of adaptation of the gut. When you eliminate something, your gut becomes less adaptable to it. When you bring it back, it might restart with some spotters. It may be that going low and going slow can help re-acclimate the gut, potentially. It's on an individual basis. Some people know if you can give it as low and as slow as you want, it's not going to change. You don't have that metabolic capacity there.

I hope that as we understand things better than microbiome better, we'll be able to maybe even do a stool test and say, “If you are the type of person that has some of these microbes there and they're underrepresented, we recommend that you go low and slow reintroducing these specific fibers.” With other people, you might say, “You don't have that capacity but we have this supplement that you can take that will reintroduce those species at the same time as getting these fibers.” I would love to see a future where rather than this stopgap measure of eliminating things and there are some conditions where you do have to eliminate like celiac disease, we could truly reintroduce these fibers and microbial and metabolic diversity that historically has existed within our gut.

You finished telling us about the fact that we might need to take a more personalized approach to nutrition, especially when it comes to the reintroduction of certain foods and a long-term like if somebody was a vegan who decided they no longer wanted to be vegan or more commonplace, what we're seeing is someone who's operating as an omnivore and is working to become more plant-based and then realizes, “I have a hard time consuming as many beans as I'm advised to eat.” It's one example. If we're thinking about shifting diet or desire to help you manage your health and create a better situation for yourself long-term, I'm wondering if there are any specific myths that you know about that you want to debunk?

I’m not sure about myths. One option that may truly help reestablish diversity and this harkens back to the Stanford study would be fermented foods, which were shown to increase diversity in the gut. This certainly needs a lot more research and study but maybe that's one pathway. Strangely, it's not the microbes that are in that food.

It's what it stimulates.

That's exactly it. There are fermentation factors that are present that serve as prebiotics for growing good bugs in the gut that are maybe natively there but underrepresented.

Could this be part of the reason that doing something like adding a tablespoon of apple cider vinegar to your diet as an example helps?

It's certainly possible. I am truly intrigued by not apple cider vinegar but vinegar at large. There's a wealth of literature on vinegar in metabolic disease. Vinegar is another name for it as acetic acid or acetate. It's a cousin of butyrate. It's a short-chain fatty acid. It's made in our gut as well as by fermenting foods. It mitigates the absorption of sugar from the gut and slows the spike in your blood of sugar like fiber and fat. Maybe that's why some cuisines add vinegar to fish and chips and why sushi rice has rice wine vinegar.

I thought it made it more sticky. It makes it delicious. I didn't realize that sushi rice had sugar and vinegar in it until I made it at home. I was like, “This isn't a recipe but can I do it without?” I tried to do it without either of those things individually but it doesn't stick together the same. You end up having roles that fall apart. I don't know the science behind it but it makes it more sticky. I wonder if you have any go-to supplements that you tend to use yourself or advise people that you're connected with either patients or in your community to consider consuming to fill their nutritional gaps?

Numbers 1, 2 and 3 are whole foods. I always stress the importance of whole foods. I am a pragmatist and I recognize trends. You and I live, eat and breathe food science. I think about this all the time. I won't speak for you. I'll speak for myself. I'm certainly not a saint. To quote Michael Pollan, “Not just eat food, mostly plants, not too much.” He also is credited as my eleven-year-old daughter taught me after her curriculum and nutrition, “Cheat every now and then.”

When you do break down and have something sweet or treat yourself and you have a couple of beers or something like that, it can also create digestive problems if you do that too routinely. Preferred supplements, are you talking about prebiotics?

If I am to do a supplement, A) It's going to be in the context of having a meal because food is meant to be in context. Oftentimes, people take supplements and think, “I've got all these good vitamins. It's going to fill the gap and things are great,” but if you're trying to support a thriving microbial community in your gut, those supplements are best taken along with all the other nutrients that those microbes are expecting. People don't often realize that.

The one supplement that I do on a routine basis is adding some additional fiber to foods. It's in the context of having cake and eating it too. If I want a bowl of ice cream, have something sweet or even something that has a lot of carbs in it, that might be refined carbs, like a bowl of rice, I'll add a little bit of fiber to that meal or I'll do a little fiber shot before. There's good peer-reviewed literature on how that fiber truly slows the absorption of sugar. You have less of an insulin spike. There is some literature support, maybe less grogginess or food coma that we experienced after meals and maybe less hangry, those dips that happen in between meals and smoothing out that blood sugar absorption through fiber.

I understand too that you offer something like that through Supergut with a little powdered packet that you can add to about anything. I understand that your team is offering our community a 20% discount at Supergut.com by using the coupon code NWC for Nutrition Without Compromise. Thank you for that. I did try the prebiotic fiber by adding it to some food and didn't notice it at all. It doesn't have a flavor. That makes it easy. I also agree with you that mostly when you take supplements, try to consume them with food. Certain supplements are recommended to take without them. For instance, if you have a bad bruise or hematoma, you might take some enzymes away from the time that you're eating food to help break down that tissue.

In that case, you're working with a doctor, nutritionist, naturopathic practitioner or something to that effect anyway. What I like to do is take mine with a protein shake because it's a great way to start the day or at least when I have my first meal a day which slightly is around lunchtime, I will have a protein shake. I can blend in some of that prebiotic fiber if I choose. I like to throw in some cranberries for their tartness and there are other benefits o some walnuts so I'm getting plant-based omega-3s.

I also take Orlo’s omega-3, which I don't necessarily have to consume with food. I also like the concept of priming my system. If you're chewing or you're tasting something, your body's getting the signal from your brain to your gut and your gut back to your brain that you are eating. It's time to get the gastric juices flowing and start digesting our food. I believe that there's something to that psychologically.

Even if I have counseled people in the past like, “Eat a handful of nuts, something small. It doesn't have to be a whole meal.” You're starting the process. You're chewing. You're getting some saliva flowing, which also brings forward the ability to begin the digestion of food or things that you're consuming. You'll get the most benefit out of the supplements that you're taking. After many years of doing this and supplements, I've heard a lot of stories but generally speaking, I tend to come back to that.

Thank you so much for joining me. I very much enjoy this conversation, getting to know more about how the gut and the brain work together to send the right signals and the fact that we might have much more happening in the gut than we ever imagined, specifically, as it relates to hormones and the representation of hormones. Perhaps that's also lending to your hormone type that we might be hearing much about in the diet world.

It's a real pleasure. I appreciate the opportunity to deliver some important messages to the world and your community. The work that you're doing is critical for that. I’m very grateful for being able to join you. Thank you.

Are there any thoughts you'd like to leave our audience with before we part?

Eat more fiber. Nobody gets enough.

I have fibervores in my house. You might want to use it. My fibervores have four legs. They are guinea pigs. All they eat is essentially fiber. You're constantly giving them vegetation. They have to chew all the time. They don't eat any animal products at all. They're full vegan little critters. They're getting our apple course so perhaps they're even healthier.

You should start saving those for yourself.

I tend to eat them too with the nut butter. I eat the whole apple aside from the stem, which is a little too fibrous for me. I'm not quite that.

It's the whole upcycling craze. It's happening within food and nutrition. All these things that we've thrown out historically are given to our guinea pigs or our animals and are probably things that we should be giving to ourselves.

Thank you so much.

My pleasure.

---

To find out more about Dr. Chris Damman, his work with Supergut and more, you can visit Supergut.com. Our audience gets an additional 20% off with checkout. Use the coupon code NWC for Nutrition Without Compromise. If you have enjoyed this episode, I hope that you'll share it with friends. If you can go ahead and give us a thumbs up or a five-star rating, that will help us reach more people with this valuable content. With that, I invite you all to raise a cup of your favorite beverage with me, perhaps it's even a protein shake with some of the Supergut prebiotic fiber. Here's to your health.

Important Links

-

Marc Washington –Better Digestion = Better Health With Marc Washington - Past Episode

-

Dr. Joseph Maroon – Balance Your Health From Square One With Dr. Joseph Maroon, Internationally Renowned Neurosurgeon, Team Neurologist Of The Pittsburgh Steelers And Ironman Triathlete - Past Episode

-

Dr. Joel Fuhrman – Become A Nutritarian To Supercharge Your Immune System And Health With Joel Fuhrman, M.D., The 7x New York Times Bestselling Author Of Super Immunity And Eat For Life - Past Episode

-

Fermentation Queen –Why Fermented Foods Is Good For Your Gut Microbiome With The Ferment Queen, Donna Maltz – Past Episode

About Chris Damman

Dr. Chris Damman is the Chief Medical 6 Scientific Officer of Supergut, where he leads scientific validation efforts and informs new product design-inspired by the potential of functional foods that harness the microbiome to transform health. A board-certified, actively practicing gastroenterologist, he holds an M.D. from Columbia University and an M.A. in Molecular Biology 6 Biochemistry from Wesleyan University.

Dr. Chris Damman is the Chief Medical 6 Scientific Officer of Supergut, where he leads scientific validation efforts and informs new product design-inspired by the potential of functional foods that harness the microbiome to transform health. A board-certified, actively practicing gastroenterologist, he holds an M.D. from Columbia University and an M.A. in Molecular Biology 6 Biochemistry from Wesleyan University.

Prior to joining Supergut, Dr. Damman worked at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, where he led its $40M gut health, microbiome, and functional food initiative. With a focus on the role of diet and microbiome-targeted therapies, Dr. Demman specialized in treating gastrointestinal, metabolic, and neurologic disease throughout his five-year tenure at the foundation. He maintains an academic appointment with the University of Washington as Clinical Associate Professor, advising the Department of Medicine and Global Health Chairs on food and microbiome topics.